With the launch of Apple Pay this past October, Apple became the latest in a string of companies – including competitors such as Google and PayPal – to launch a mobile payment platform. Hopes are high for the emerging mobile payments industry: according to new research, the global market for mobile payments is expected to grow to over $700 billion by 2017.[i] The problem is, our understanding of factors that contribute to platform adoption and growth remains poor and fragmented across multiple disciplines.

Indeed, the multitude of mobile payment platforms launched over the past decade have one thing in common: they have all failed to reach what we call critical mass – the sufficient number of adopters needed to create self-sustaining growth. So why have companies that have generated so much hype, failed to generate any real success stories up until now?

Above all, multi-sided platforms like mobile payment platforms are notoriously complex. Their growth depends not only on consumer adoption, but also on the participation and goodwill of banks, merchants, card issuers, and mobile operators. These groups of stakeholders need to grow simultaneously since the value of the platform for any user on one side, depends on the number of users on the other side. The challenge for platform owners is therefore to create the kind of perfect storm of networks effects[ii] that will lead to critical mass, ignition and take-off.

However, according to our new research “The Impact of Openness on the Market Potential of Multi-sided platforms: A Case Study of Mobile Payment Platforms"[iii], a platform’s level of openness can make or break its chances for success – to the point where some platforms are doomed to fail.

Not surprisingly, a big factor for the success of any new venture is market potential – the bigger the number of prospective clients you can reach, the higher your chances for success. What is surprising, however, is that many mobile payment platforms are designed in such a way that they restrict participation to a prospective user base that will be, even in the best-case scenario, too small to generate the network effects needed to reach critical mass. In other words, their degree of openness can doom their venture right from the start.

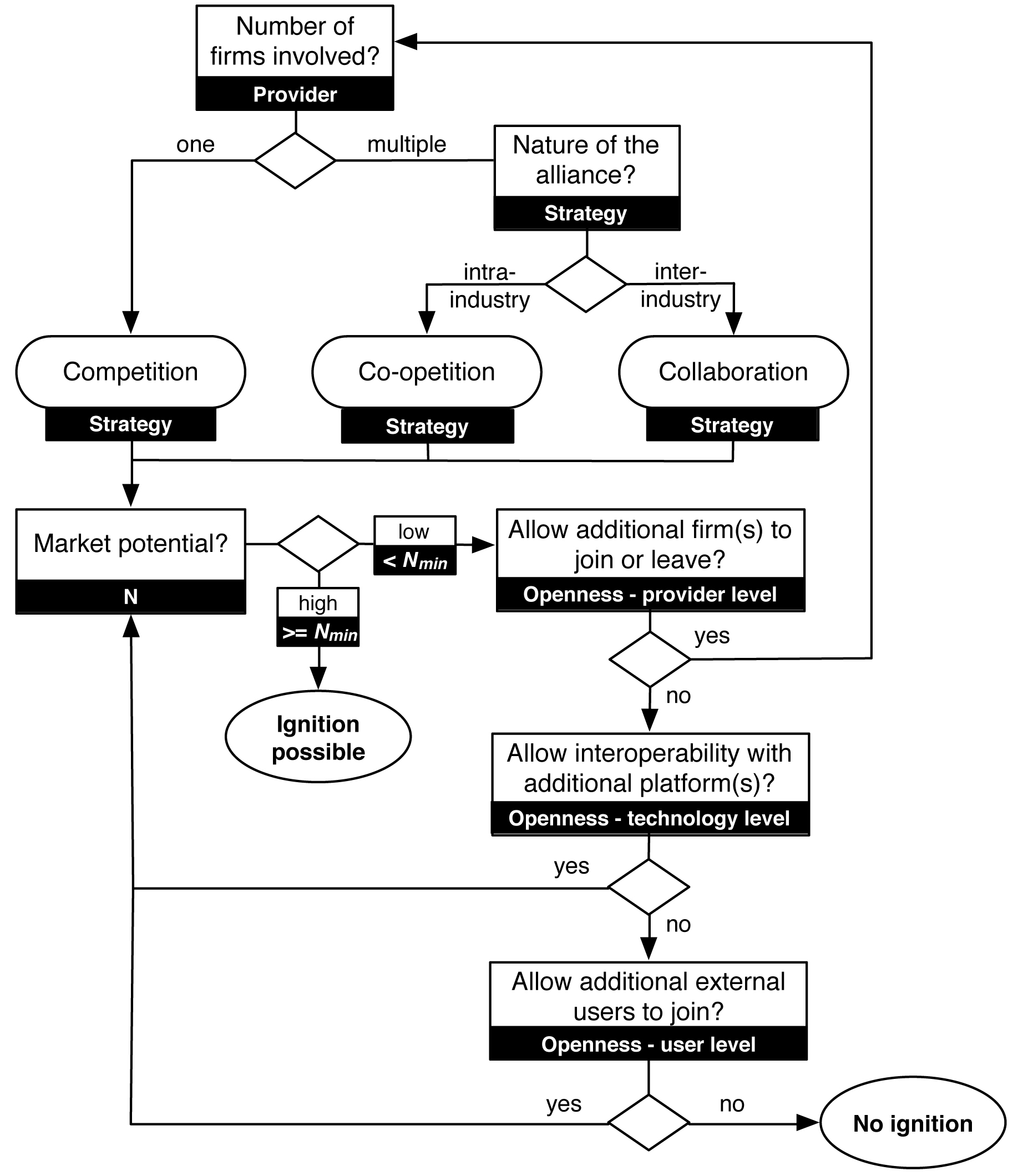

Indeed, platform providers must decide early on to what extent their platform will be open or closed, at three distinct levels. First, at the provider level, openness is defined by whether or not additional providers are allowed to join. At the technology level, openness depends on how interoperable or incompatible the platform is with other platforms and related technologies. At the user level, openness is concerned with making the platform accessible in indiscriminant ways to new users.

So, how do these openness decisions at the early ignition stage influence a platform’s market potential?

Openness at the provider level

Some platforms – like Apple Pay – are closed at the provider level. In these cases, platforms are provided by a single firm that vertically integrates all the different resources required. The Apple App Store, with more than 1M applications, is a good illustration of such a platform and illustrates the level of success that can be achieved by firms who have the means to achieve ignition on their own. Other platforms are provided by an array of horizontally collaborating firms with specific roles and responsibilities. In these cases, platform providers have to decide on the degree of openness at the provider level.

One option is Co-opetition, which means that competing firms within the same industry decide to collaborate and provide a horizontally integrated platform. Softcard (formerly ISIS Mobile Wallet), for example, is a joint venture operated by three major American operators – AT&T, Verizon Wireless and T-Mobile – who have agreed to invest more than 100 million to enable their customers to pay with their mobile phones.

The good news in this case is that by opening the provider level to nearly all intra-industry firms, Softcard is in a position to reach a high market potential. The catch, however, is that mobile payments through Softcard require the user to have a NFC (Near Field Communication) enabled phone, and as of 2013, there were about 20 million such handsets in the U.S. market. There is also a technological lag at many points of sale across the country. So, at the end of the day, technical requirements are still limiting the market potential of initiatives like Softcard that are open to intra-industry firms at the provider level.

Another option is Collaboration, whichmeans that multiple firms form different industries collaborate to provide a horizontally integrated inter-industry platform. A good illustration of this is the collaboration between the Canadian MNO Rogers and CIBC Bank, who started offering a mobile payment platform to their clients in November 2012.

The bad news for collaborating platforms is that only users belonging to the intersection of the market shares are eligible to join the platform. For example, Rogers’ market share is 34% of the mobile telecom market, while CIBC’s is approximately 18%. Therefore, the total market potential for this solution cannot be more than 18% of the Canadian population. Keeping this in mind, it’s not surprising that adoption rates for this platform were reported as slow.

In November 2013, however, Rogers obtained a banking license and has announced plans to issue its own credit cards, which will likely end the collaboration with CIBC. Strategically, this makes sense since their market potential will go from 18% to 34% of the Canadian population. This case illustrates well that adding an inter-industry firm at the provider level often leads to lower market potential.

Openness at the technology level

Three main players compose the Korean mobile telecommunication industry – SK Telecom, KT, and LG U+ – all of which launched mobile payment platforms in the early 2000s, based on proprietary infrared (IR) solutions. All three initiatives met with the same fate: failure.

The problem was: all three platforms were closed at all three levels. At the provider level, none of the competing firms wanted to partner with each other. Therefore, at the technology level, all the competing platforms were based on proprietary technology: in other words, merchants would need to be equipped with multiple payment terminals, one terminal for each of the payment platforms. Despite trying to roll out hundreds of thousands of proprietary merchant POS terminals, each of the platforms failed to reach critical mass at launch.

The situation changed, however, when in 2006 NFC emerged as an interoperable standard and overnight all the rival proprietary solutions became interoperable with each other. This development created a standard for the South Korean payment ecosystem: merchants no longer needed to install an additional device; they simply needed to upgrade their terminal to be NFC compatible. Opening at the technology level with competing platforms has since dramatically increased the market potential of each of competing platforms. SK Telecom, for example, was able to register 2.6 million users in 2007.

Openness at the User Level

When Google first presented its mobile “Google Wallet” in partnership with Citi, Mastercard, Sprint, and First Data in May 2011, its market potential was severely diminished because of openness issues at the user level. Only consumers with Nexus S 4G sold by Sprint could join the platform, as it required a specific kind of NFC chip. Theoretically, Sprint’s market share (55 million subscribers in 2011) should have helped to recruit many potential consumers. However, the dependence on one unique mobile device decreased significantly Google Wallet’s reach. Samsung only sold 512,000 Nexus S 4G in the U.S. market between 2011 and 2012, of which not all phones were Sprint registered. In addition, other American operators refused to join Google Wallet, further hindering its ability to reach critical mass at launch.

Since then, Google has opened its platform to additional mobile phones and thereby increased its market potential. Nevertheless, the current number of mobile phones compatible with the solution and non-participation of other major operators still jeopardizes the market potential of Google Wallet.

From a practical perspective, our study is of paramount importance to practitioners involved in making openness decisions about multi-sided platforms. Indeed, it is necessary for platforms to have the minimum market potential necessary to ignite and succeed. However, while greater openness is usually favorable to larger market potential, there can also be negative consequences to too much openness. Ultimately, this needs to be balanced carefully by managers. Our decision model may be able to help practitioners decide on openness strategies that maximize market potential and hence the likelihood for success.

[i] https://www.gartner.com/doc/2484915/forecast-mobile-payment-worldwide-

[ii] In economics and business, a network effect is the effect that one user of a good or service has on the value of that product to other people. When a network effect is present, the value of a product or service is dependent on the number of others using it.

[iii] “The Impact of Openness on the Market Potential of Multi-sided platforms: A Case Study of Mobile Payment Platforms” by Jan Ondrus (ESSEC Business School) with co-authors Avinash Gannamaneni (ESSEC Business School / MIT) and Kalle Lyytinen (Case Western Reserve University).