Why are some nations wealthy while others remain relatively poor? Today’s increasing rates of economic globalization are giving this question new importance. However, as Arijit Chatterjee explains, an oversimplified analysis has thus far dominated discussions.

“As human beings,” he explains, “we have a tendency to simplify complex things by creating overarching categories and classifications. This means highlighting differences between the “East” and the “West”, regrouping countries into larger entities like Europe or Asia, and cataloguing them as either “developed” or “developing” nations. Parsimony has its benefits but can also lead to erroneous conclusions. When we talk about economic globalization, our analysis more often than not fails to take a closer look at the economic activity inside individual countries.

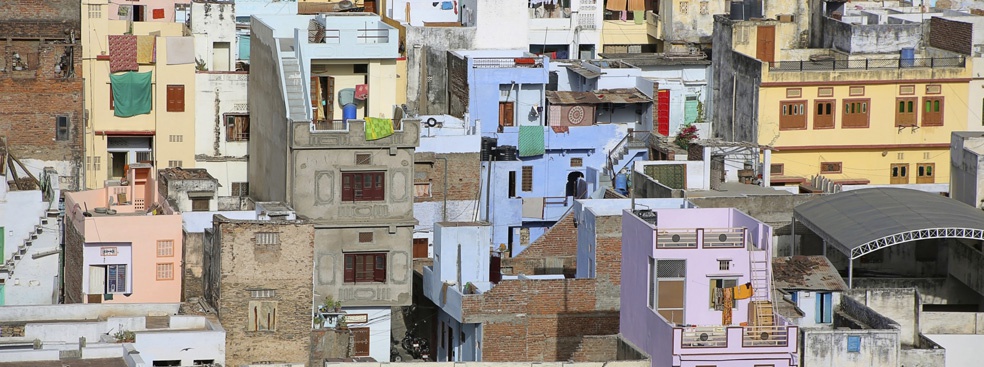

Indeed, important disparities between regions are a reality within many national borders. For example, interprovincial inequality has increased in China where economic growth has centered on the coastal regions and southern Brazil accounts for more than 75% percent of the GDP. For a multitude of reasons, India’s economic growth has also progressed unevenly across the country, with regions in the east of the country remaining poorer on the whole than the regions in the west and the south. Fifteen years ago, Jairam Ramesh, now the Union Minister for Rural Development, had remarked that if one drew a longitude through the North Indian city of Kanpur, she would find that the region to its west grew prosperous with every passing year, while the region lying to the line’s east remained significantly poorer.

Why this divide between the east and the rest? Explanation of this phenomenon needs careful consideration of a multitude of factors. Above all, the answer to this question can be found in India’s complex colonial history. “East India was the first area to be colonized by the British, around 1757, and the land revenue systems set up here were different from those systems set up in the West and the South,” explains professor Chatterjee. “The biggest factor for the region’s enduring poverty was an initial lack of private property rights. Absentee landlords did nothing to improve infrastructure and development in the East has lagged behind ever since.” Apart from history, other causes include policy decisions, presence (or absence) of business communities, infrastructure, and access to resources.

Ramesh’s observation about these economic inequalities has big implications today. India’s position as an emerging economy and its impressive growth rate has created greater disparity within the country - for the time being at least. And internal cultural divisions have accompanied the economic ones. “India is a remarkably diverse country. There are no fewer than 22 official languages recognized by the constitution, not to mention the country’s many different cultures, cuisines, religions, and traditions. The political structure is federal and with so much internal diversity it’s natural that the inter-state migration for seeking economic opportunities elsewhere had not always been without issues such as usage of language, celebration of festivals, and assimilation with local traditions.”

While divergence in prosperity – the widening of the gap between rich and poor regions – has been an economic reality in India in the recent past, Professor Chatterjee would argue that it cannot continue. The prospects of political instability are too high in a young country where more than half of the population – 600 million people – are below the age of 25. He believes that this phase of divergence has reached a peak, regional political discourses of grievance are becoming ones of aspiration, and convergence is slowly taking shape.

“By whichever method you arrive at poverty estimates – current income or calorific intake – the numbers are staggering. A 2011 Oxford University Report that measured poverty by the three dimensions of education, health, and standard of living concluded that 650 million people in India are poor and a vast majority of them are living in “East of Kanpur.” A planning commission benchmark of 32 rupees (60 cents) of income a day for access to government’s many anti-poverty initiatives was scrapped after intense criticism from various quarters. “How poor can you remain? There is really nowhere to go but up from this point. We are now in a period of catch up: differences in productivity are not inherent, people can be trained and made employable or they can become entrepreneurs, health services can be improved, and basic infrastructure such as roads and electrification can increase mobility and connectivity that increases access to markets.”

“Divergence and convergence is something observed throughout history,” he adds. “If you look at large entities like the Habsburg Empire, the United States, or the United Kingdom in their periods of economic growth you will see a similar pattern: there is divergence in the beginning which is exacerbated by rapid growth, and then gradually they enter phases of convergence when poorer regions gradually achieve their aspirations of relative equality.”

Signs of convergence are already becoming apparent in traditionally poorer Indian states like Bihar, which is now growing at the impressive rate of 13 % even at a time when headlines in the media are constantly spelling doom for the world economy. This situation is creating tremendous opportunity for entrepreneurs, large and small businesses alike, in regions that have historically had slower rates of economic growth.

“In times of convergence, opportunities are the greatest in these lagging areas. There is huge opportunity to fill the institutional voids, develop infrastructure, and urbanize. Businesses are currently developing train networks, rural roads, and new modes of public transportation, constructing high-rises and new airports, and developing world-class research centers. And from the perspective of a company, branching out into new territory can pave the way to new ways of achieving product differentiation to appeal to new markets. So when companies ask themselves the question ‘where should we go?’ the draw of Eastern India has increased.”

These poorer regions are home to millions of people and are frequently some of the most densely populated areas in the world. This translates into millions of dreams and aspirations that can only be met through economic growth, infrastructure development, and investment. And while this means enormous resource depletion and bigger environmental problems for the world at large, it is also encouraging innovative ideas to respond to this new demand while having lesser impact on global resources.