The meaning of philanthropy has evolved over the centuries. In what sense is it still a contested concept?

Philanthropy has its detractors and its supporters, rarely leaving one indifferent. Like many other abstract ideas, philanthropy has been the subject of endless arguments since its appearance in the 18th century. Its meaning has morphed over time, depending on the social, cultural, and political context, and on the person using it. While philanthropy was less present in France in the 20th century due to the rise of government social benefits, it regained a certain popularity in the beginning of the 21st century, as private donations began to complement public funding in many domains.

How has the concept evolved?

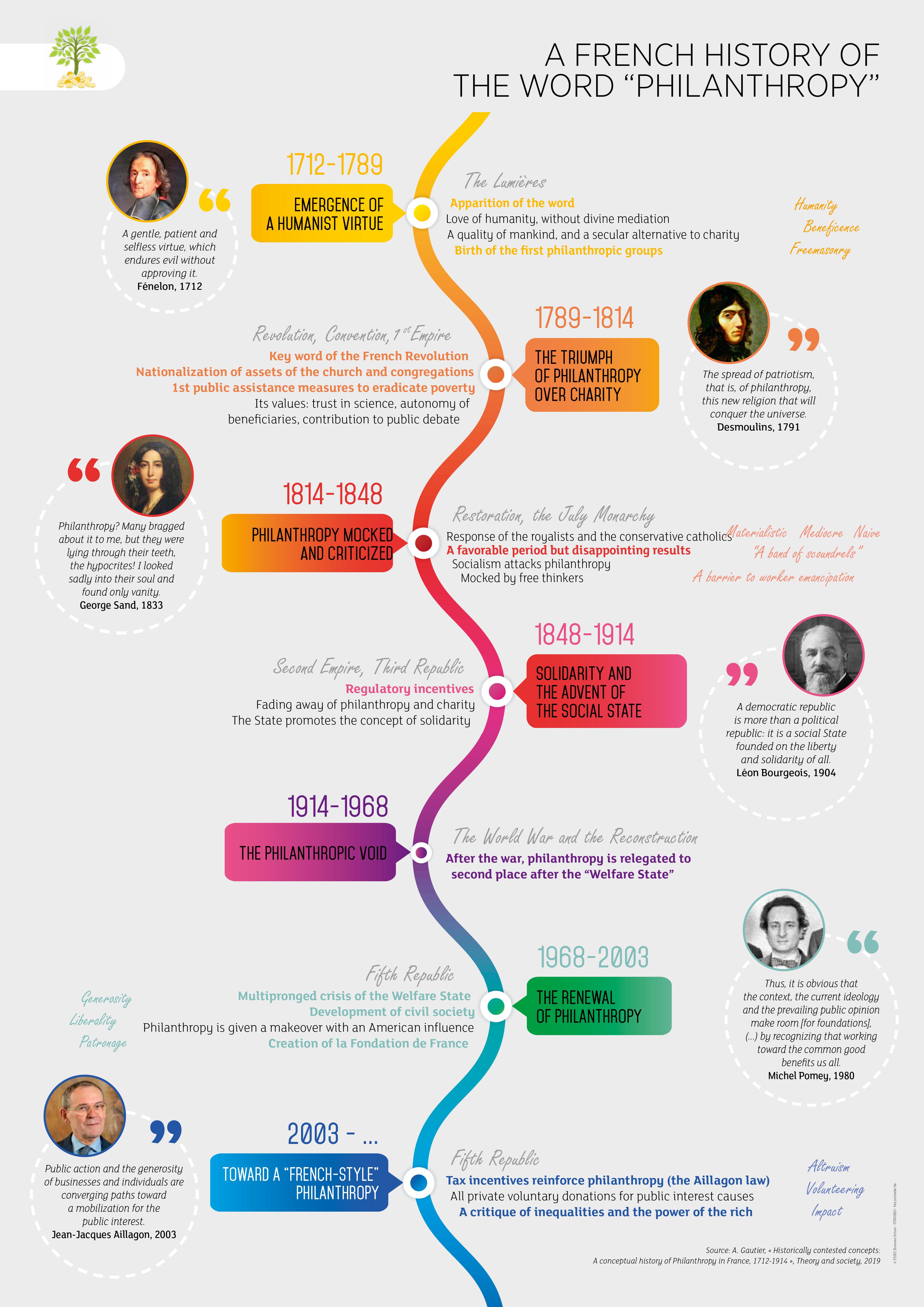

It was the theologist Fenelon who first recorded the word “philanthropy” in French. He defined philanthropy as “a gentle, patient and selfless virtue, which bears evil without approving it”. For encyclopedists like Diderot and Voltaire, who considered mankind as good by nature and society as able to be perfected, philanthropy is a virtue. While the definition of “philanthropy” was initially agreed upon, it gradually became a secular alternative to Catholic charity. In this sense, philanthropy was considered to replace the love of men as creatures of God with the love of mankind for mankind.

In 1789, inspired by the novel ideas of the Enlightenment, philanthropy triumphed and became a buzzword of the Revolution. During the reign of Napoléon Bonaparte, private philanthropic initiatives flourished in many areas: building decent housing and clinics, protecting orphans, distributing food vouchers, vaccinating against smallpox, campaigning to end slavery and the death penalty… Financed and led by the era’s progressive elites, the initiatives sought to make concrete and lasting improvements in the lives of society’s most vulnerable. Philanthropy set itself apart from traditional charity with its regard for science, pursuit of autonomy for its beneficiaries, and participation in public debate.

The concept became more divisive after 1814. During the Restoration, royalists and conservative Catholics sought to rehabilitate charity. The conservatives accused philanthropists of being vain, materialistic, and having abstract ideas. For Chateaubriand, philanthropy was “nothing else but the Christian idea of charity overturned, renamed, and too often disfigured”. Philanthropy also appeared insufficient for addressing the magnitude of the social problems caused by the Industrial Revolution. The “band of scoundrels” (filous en troupe) were caricatured in Flaubert’s novels and in the newspapers for their naivety, mediocrity, and careerism. Starting in the 1840s, philanthropy suffered a new blow, this time from the left: socialist thinkers considered it a hypocritical mask, an obstacle to the voluntary emancipation of workers, or a way for the capitalist elite to disguise their exploitation of the proletariat.

From 1848 to World War I, philanthropy lost its luster and endured competition from a new concept: solidarity. Contrary to philanthropy, which is based on individual morality, solidarity implies a legal constraint: it should be enforced by law for all, funded by tax revenues. Looking for a third way between revolutionary socialism and liberal capitalism, the Third Republic made solidarity a key concept. Despite the French dread of any form of “legal charity”, the Republican State ended up instituting the first “social laws”: free medical assistance, support for work accidents, help for the elderly and the vulnerable. Philanthropy and charity are still present, but are relegated to the background.

How does this history clarify current debates?

First, it is striking to note that philanthropy has a rich history in France and that this history is intertwined with the treatment of social issues. The French Republic, founded after the 1789 Revolution, tried to start a secular, progressive alternative to Christian charity by promoting the concept of philanthropy. As French society became more secular, the rivalry between philanthropy and charity lessened, and in the end the concept of solidarity was retained, bringing with it the first measures of public assistance financed by taxes rather than donations.

However, philanthropy was revived at the beginning of the 21st century. Abandoned and considered old-fashioned with the rise of the social programs after 1945, the word “philanthropy” was re-introduced when the French social welfare system was considered in crisis. How did this revival come about? There was certainly the influence of “philanthro-capitalism” and the power of Gates’ and Buffett’s Giving Pledge in 2010, but the American influence does not account for everything. A “French-style philanthropy” has been on the rise for around 15 years. More obvious in the public sphere, it has been encouraged by the State thanks to several landmark laws that have made it more legally and fiscally appealing. Far from being two rivals in the management of public interest, philanthropy and the State continue their common history, between encouragement and control, but with new balance.

Contention has not disappeared with the revival. Rather, it has resurged, notably with the funds raised following the Notre-Dame fire in Paris. Arguments first used by socialist critics in the 19th century were repeated, like pointing out the hypocrisy of wealthy people who become philanthropists to compensate for their predatory business ventures. There were also new arguments around the question of inequalities and the disengagement of the State. On another note, a populist and nationalist one, philanthropy is sometimes seen as an enemy of the people, a foreign agent, coming from the world’s financial elite. The most striking example is found outside of France: George Soros, harshly blacklisted in Hungary by the Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, for his defense of migrants during the 2015 crisis. It will be interesting to see how the sector of philanthropy and its champions, for whom it is a pledge of pluralism and social innovation in open societies, respond to these new arguments.

Further reading

Gautier, Arthur (2019). Historically contested concepts: A conceptual history of philanthropy in France, 1712-1914. Theory and Society, 48(1), 95-129.