Giovanni Pagliardi, PhD student at ESSEC Business School, and Prof. François Longin, Prof. of Finance, share research on 32 countries to disentangle the different concepts of political risk and economic policy risk and provide a ground-breaking decision-aid tool for international investment and development funds.

___

When the risk is high, we go for low – but what risk?

Imagine you are an investor, a government, a trader, a company – and you have ten billion dollars to invest. You take two countries – France and Turkey – the former ranked among the world’s best in terms of political stability, the latter the victim of a recent coup, internal tension, and turmoil in neighboring Syria that threatens to spill over the border. The question is: which one would you feel more comfortable with in placing your hard-earned ten billion? Instinctively, the answer would most probably be France.

True, Turkey displays an incredibly high level of political risk – with its long-term uncertainty and current troubles, it is straightforward to understand why – consequently appearing among the very last in The Economist Intelligence Unit international political risk ranking. With respect to France, the gap is huge. However, with a position of mid-way through the rankings as far as economic policy risk is concerned, Turkey performs better than France. So who do you now chose to invest in and reap those returns? The same question was likely asked of Spain in the period 2014-2016, when the country faced high political turmoil and difficulties in forming a stable government. As reported in a recent article on Bloomberg, however, Spain in those same two years out-performed the Eurozone as far as GDP growth was concerned despite its political turmoil. Why? Because of effective economic reforms implemented in the country.

New work on a sample of thirty-two countries by research fellow Giovanni Pagliardi at ESSEC Business School suggests that such decisions deserve deeper thought before being made. He disentangles the different concepts of political risk and economic policy risk, theformer referring to government instability, information access, transparency and political event risk; the latter referring to the actual implementation of the economic reforms by the government, whether "good" or "bad" economic reforms for the economy of the country. He provides evidence that these two sources of risk at the international level display, surprisingly, very low correlation. With the results, he then went on to analyze the impact of these two sources of risk on sovereign default risk and international financial markets co-movements.

Disentangling risk gives a surprising picture

Traders, economists, politicians and international bodies and organisations would all like to have something tangible to hold onto when on the brink of making heavy investment or development aid decisions. This time, it seems to be the case: by measuring and comparing political risk and economic policy risk. Pagliardi’s leitmotiv for his research was sparked by a realisation that no-one had formerly disentangled these two sources of risk or given precise definitions to them. Indeed, if political risk and economic policy risk are not differentiated, and only a more general political variable affecting the financial markets is considered, it implicitly means that political risk and economic policy risk have the same impact on financial markets.

However, a surprising result that reinforces his findings and the need to disentangle these two sources of risk was that they have a differential impact on the world of finance. In his paper, Pagliardi shows that more effective economic policies and lower political risk translate into lower sovereign default probabilities. In addition, he provides evidence about the very high performance of trading strategies that invest money in countries that are better ranked as far as these two risk factors are concerned. Very interestingly, this research sheds light on the different relative magnitude of the effects stemming from policy and institutional risks on stock market performance and sovereign default risk, and how combining these information together can be beneficial for an investor. Taking the two risks into consideration and dissassociating the two can help us to dive into the uncertainty driven by the current political situation and events and resurface with a clearer, truer view of ther bigger pricture from which to base our investment, trading and political decisions.

Of politics, uncertainty and finance

This is important. Exceptionally so in today’s world of Brexit, cooling US-Russia relations, forthcoming elections in France and Italy and China’s road to what some of us might call “full democracy”. For political decisions, institutional issues and economic reforms are also often assessed with respect to the impact that they have on financial markets.

Indeed, it is generally thought that political risk is the main aspect affecting sovereign default risk. Hence, a stakeholder may think that a deterioration of the institutional situation of country A with respect to country B, or the weakness of government A with respect to government B, can be associated with a future divergence of the probability of default priced by the market of these two countries.

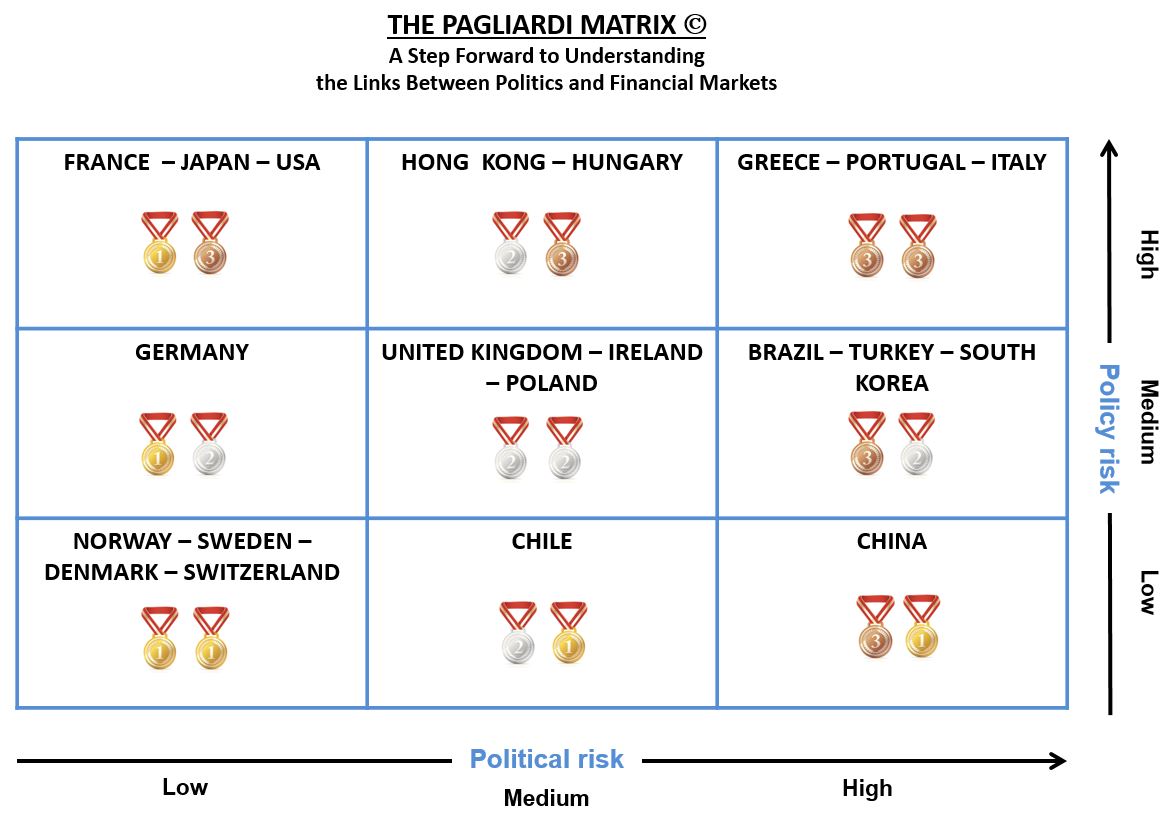

However, we should ask ourselves what political risk is exactly and how it can be defined precisely. Pagliardi’s research findings show how to disentangle the different sources of risk embedded in the notion of politics and stemming from the impact that politics has on the world of finance: there are countries with high institutional risk but low policy risk, and also countries with low institutional risk and high political risk. In these cases, which can be identified clearly thanks to the Pagliardi matrix, a useful and innovative tool developed by the author, political uncertainty needs to be further investigated in its different components - institutional and economic policy risk- since the latter can convey different information and may point in opposite directions. Disentangling them and assessing their impact separately becomes therefore crucial. Pagliardi's research shows the differential impact of these disentangled risk factors on stock markets and credit default swaps.

Benefits – for all

The benefits of this research and a subsequent model – the Pagliardi Matrix – are multiple. Professionals in the financial field, economists, politicians and international organisations can assess and predict more precisely which countries are becoming riskier and with higher default probability with respect to other countries by looking to their relative economic policy risk and institutional risk. Their decisions on which countries to invest in can be shaped accordingly. G. Pagliardi’s work also tests the pairs trading strategy at the international level, showing that returns are strongly affected by his political risk variable. Traders and investors can thus more clearly shape strategy to optimize success and be able to consistently beat the market generating high returns by choosing the countries in which to invest according to these disentangled political risk factors, as extensively shown in Pagliardi's research.

One essential lesson: ignoring variances in political risk and economic policy risk would lead to completely wrong conclusions about the relationship between politics and finance and the impact of the former on the latter. Rather than assume that “when risk is high, aim for low”, wiser to ask yourself what risk before letting go of your ten billion.