With Estefania Santacreu-Vasut

Basing their research on a groundbreaking simulation tool, ESSEC Professors Estefania Santacreu-Vasut and François Longin investigate the influence of gender stereotypes on investors’ financial decisions.

Un-blinding gender in finance

Glance across today’s business school classrooms and you will see as many, if not more, female students as male. But the reality is that few female students choose to specialize in finance during and after their studies, even when they tend to perform generally better in the classroom. Finance curricula tend to be gender blind and this is, moreover, most probably the case of the financial industry as a whole. This observation pushed Profs. Estefania Santacreu-Vasut and François Longin to investigate students’ reactions to gender-related news in the context of finance. And in order to do that, they decided to follow an experimental approach using a simulation tool, baptized SimTrade, whose main advantage is to contextualize a financial experiment with social factors.

Combining François Longin’s experience in teaching finance and in studying financial markets with SimTrade together with Prof. Santacreu-Vasut‘s research interest in gender economics, they decided to team up to “un-blind” gender in finance from the classroom to the trading floor within the framework of a Gender & Finance project.

Undoing barriers to finance

From the labor market to the political arena, women have long-since faced barriers in their access to finance. Economists explain that one of the reasons why women face these barriers in accessing the financial market originates from the fact that women are over-represented among the poor: poverty implies that women tend to lack collateral, which prevents them from accessing loans in the traditional financial industry, thereby leading them to be considered as “un-bankable”. Women also tend to be less financially literate than men, which also limits their participation to the economy and their ability to make financial decisions.

Another explanation is that these barriers are not the result of economic inequality but are rather rooted in cultural, linguistic and historical practices including patrilineal inheritance laws, or agricultural specialization, for example. These may have shaped economic specialization together with the emergence of gender roles. Finally, experimental approaches investigate whether gender inequality is explained not in terms of reflecting barriers but in behavioral differences that may include, for example, females exhibiting higher risk-aversion and lower taste for competition.

Female students in finance: high achievers, low pursuers

Research began by looking at a student population* characterized by a good balance between female (53%) and male students (47%) and followed their performance over the course of the academic year. Results showed that both female and male students had similar success rates: 92.99% for female students and 90.48% for male students. However, on average, female students performed better than male students, the average grade standing at 14.37/20 for female students and 13.28/20 for male students – a statistically significant difference. Female students performed also noticeably better than male students at the top-end of results (students with the maximal grade of 20/20): 32 female students compared to only 14 male students. So much for female out-performers – although they manifestly achieved better than male students in the classroom, it was seen that fewer female students decided to pursue their studies in finance – 21 compared with 43 male students. Looking a few years ahead within the scope of the same studies track, the same difference is observed for the choice of career: 41 female former students and 76 male former students were observed to be working in the financial sector after graduation (graduated classes 2013-2016).

To summarize, female students perform better than male students in the classroom but are fewer to decide to continue to study finance and to embrace a career in finance.

So why is that? The answer partly lies in the fact that the narrowing of gender gaps since the beginning of the 20th century has been spectacular, in particular in the labor market. While the overall gender gap in labor force participation has narrowed, it has done heterogeneously across occupations. That is, the gender gap varies across certain jobs. One of the latest studies regarding these gaps argues that part of the difference is directly related to work organization (Goldin, 2014). Occupations in the corporate, financial and legal industries, where temporal flexibility is lowest, tend to lag behind in achieving greater gender equality.

Another reason why the lack of temporal flexibility hurts women the most relates to the allocation of time within households, itself related to gender roles (Hicks et al. 2015). Indeed, extant research in the economics of time use and household economics shows that women do significantly more household labor and care giving, regardless of whether they work or not on the labor market. This would explain why women may self-select themselves into occupations where temporal flexibility is highest, and disregard those, among which finance is a prominent example, which are less flexible.

Finally, another explanation that can explain why women do not choose finance as a career may be directly related to cultural expectations regarding gender roles that will tend to orient female students towards certain career choices. These cultural expectations may permeate our society through media and entertainment such as movies like “The Wolf of Wall Street”.

Simulating the real way

In addition to Profs Longin and Santacreu-Vasut’s statistical study on the performance and orientation of students, they also carried out an experiment using a simulator to examine the influence of gender stereotypes on financial decisions. Do financial markets care about gender? How do investors react to gender related news? And do investors suffer from gender stereotypes that may influence their investment performance? The tool, SimTrade, was developed by François Longin as an original teaching and learning platform that takes students through a typical 12-hour day of trading, compounded into 10 minutes. Play takes place on international markets, providing simulations in which learners can buy and sell stocks, a mathematical model based on Monte Carlo simulation techniques to simulate realistic strategies of other traders, and also firms whose stocks are traded. By simulating both markets and firms, “SimTraders” can have an impact on the market in terms of market prices and transaction volumes.

To study the gender issue in finance, a simulation called SunCar was developed in which a solar-powered car manufacturer’s future is about to change with the nomination of a new CEO. The surprise? A random selection of either a new male or female CEO. By embedding this in the game, the simulation enables the contextualization of the trading experience within a social environment that includes gender as a relevant dimension. In this way, participants in the experiment were provided with the opportunity to “test their gender stereotypes on the trading floor.”

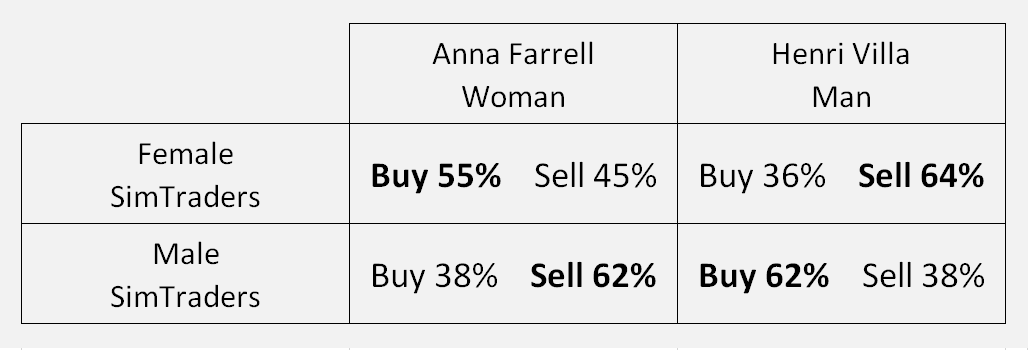

The results from the experiment provided statistics of trading activity by “SimTraders” according their gender (female or male) following the nomination of the new CEO (female: Anna Farell; male: Henri Villa).

When Anna Farrell – a woman – was nominated in the simulation, female traders reacted more positively to this announcement. Inversely, male traders reacted more negatively. When a male CEO was nominated, results were the opposite.

So far, results suggest a very interesting pattern in trading behavior related to the identity of the CEO but also of the trader. In particular, what seems to matter is not whether the elected CEO shares the gender of the trader, a situation described as homophily – afeature of social interactions related to the fact that interconnection tends to be more frequent among individuals that are similar to each other, rather than among dissimilar individuals. The concept can be applied to different dimensions such as gender, as well as age, religion, and ideology. Interestingly, homophily reflects biases that can be driven by preferences or information, for instance, risk-averse preferences. Network formation also plays an important role in explaining the persistence of homophily in the long term. In this article’s experimental setting, investor homophily (students’ preference to see the appointment of CEOs of their same gender and buy shares when this is the case) may reflect some of these biases, as well as the fact that the participant may identify with the scenario more when the CEO appointed shares their gender. Importantly, homophily permeates social interactions and may also operate outside of the trading simulation – in the financial corporations where recruiters may favor the recruitment of their own gender – thus reinforcing existing barriers.

Why finance needs women

There are three broad reasons why it is important to increase female representation in the finance field. First, from the perspective of efficiency, if women are not accessing this labor market due to barriers, it means the industry is wasting a pool of talent or, alternatively, that human capital is not well allocated. In this light, ensuring equal opportunity in accessing the financial industry and decreasing barriers would be a win-win situation for all. The second reason is distributional. Inequality itself may be detrimental. One potential reason lies in the hypothesis that women’s decision-making characteristics differ from that of men’s, a subject that has been widely debated regarding women’s participation on corporate boards. If this is the case, diversity could indeed bring different attitudes and perspectives that could be beneficial to the financial market. Finally, and not the least, the third reason is ethical. Decreasing barriers to develop capabilities, as explained by Amartya Sen, is valuable by itself and offers a different perspective on what economic development means.

From a purely quantitative standpoint, recent estimates point to significant gains being achieved from increased gender equality. For instance, a recent study from the McKinsey Global Institute, 2015 quantifies the gains from gender equality to adding $12 trillion to global growth. While such studies focus mostly on economic gains, these benefits can also be symbolic and qualitative in nature as such advances may foster trust in the potential for anyone, regardless of gender, but also of other socio-demographic characteristics, to thrive.

Among other economists, Duflo, 2012, have carried out research that suggests that role models play an essential part in encouraging emulation. Thankfully, role models in the financial and leadership fields for younger generations to follow already exist. In the vanguard of female presence are the figures of Janet Yellen, head the Federal Bank, or Angela Merkel and Hillary Clinton, in the political arena. Moreover, Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, is one of these leaders who is actually pushing the gender equality agenda.

*1st-year ESSEC Business School, compulsory Financial Management course, with a minimal grade to pass the course set at 8/20 and the maximal grade at 20/20.

Useful links:

- Visit Prof. François Longin’s blog

- Visit Prof. Estefania Santacreu-Vasut's blog

- Learn about financial markets with the SimTrade simulator

- Preview Prof. Longin's recently published book Extreme Events in Finance: A Handbook of Extreme Value Theory and its Applications, Wiley