Karoline Strauss, Professor of Management at ESSEC Business School and expert on proactivity shares her research - When does proactivity have a cost? Motivation at work moderates the effects of proactive work behavior on employee job strain - undertaken with Sharon Parker and Deirdre O'Shea to determine if and when showing initiative might drain employees’ resources and lead to stress.

Why the consequences of proactivity are worth investigating

As organizations face uncertainty and rapid change, there is an increasing focus on encouraging employees to work in a proactive way: for a proactive workforce takes initiative, anticipates changes, contributes to innovation and competitive advantage, and builds a positive future for themselves and the company. In short, they make things happen. And those who make things happen perform better in their jobs and advance more quickly in their careers.

On the surface then, proactivity seems to be the happy matter of both employees and management alike – everyone wins. But what is the potential cost to employees? How might being proactive affect their stress levels and well-being? These are important questions, not least because if being proactive takes an undue toll on individuals, then it might not be sustainable over the longer term.

Intrigued by the lack of research on the effects of proactivity on employee well-being, Karoline Strauss, together with fellow researchers Sharon Parker and Deirdre O'Shea, decided to look into this potentially darker side to proactivity and to study, empirically, when being proactive can go askew and cause stress at work.

How proactivity impacts the workforce

Proactivity refers to self-initiated efforts to bring about change – or make things happen – in order to improve the status quo: a behaviour that is of special importance in uncertain or unpredictable environments where it is not possible to identify every eventuality and pre-determine specific role requirements. A current buzzword is agile. Another – disruption: a proactive workforce, well-versed in forward thinking and adaptability, fits these two scenarios well.

But the bottom line is that attempting to bring about change in organizations requires effort, cognitive skills, and commitment. It comes at a cost that can sap one’s personal resources – because the outcomes of these efforts are uncertain, because of potential resistance and conflict with others, because of the need to manage one’s emotions while trying to stay on course, or because difficult decisions have to be made. And when these costs outweigh the resource-producing benefits proactivity may bring to the individual – self-fulfillment, better working conditions, clearer vision – it is the key factor of motivation that counts.

Key factors: autonomy and control

Karoline Strauss and her fellow researchers decided to identify what factors tip proactivity from being a source of positively empowered achievement to a possible negative burden and source of stress for the individual. In order to do that, they focused on what motivates individuals in their work: controlled or autonomous motivation. Controlled motivation involves being driven by both external pressures such as gaining rewards or avoiding punishments, and internal pressures – gaining approval, recognition or avoiding feelings of guilt and shame. Autonomous motivation, on the other hand, reflects a sense of interest in, and enjoyment of, an activity, or the value we find in it.

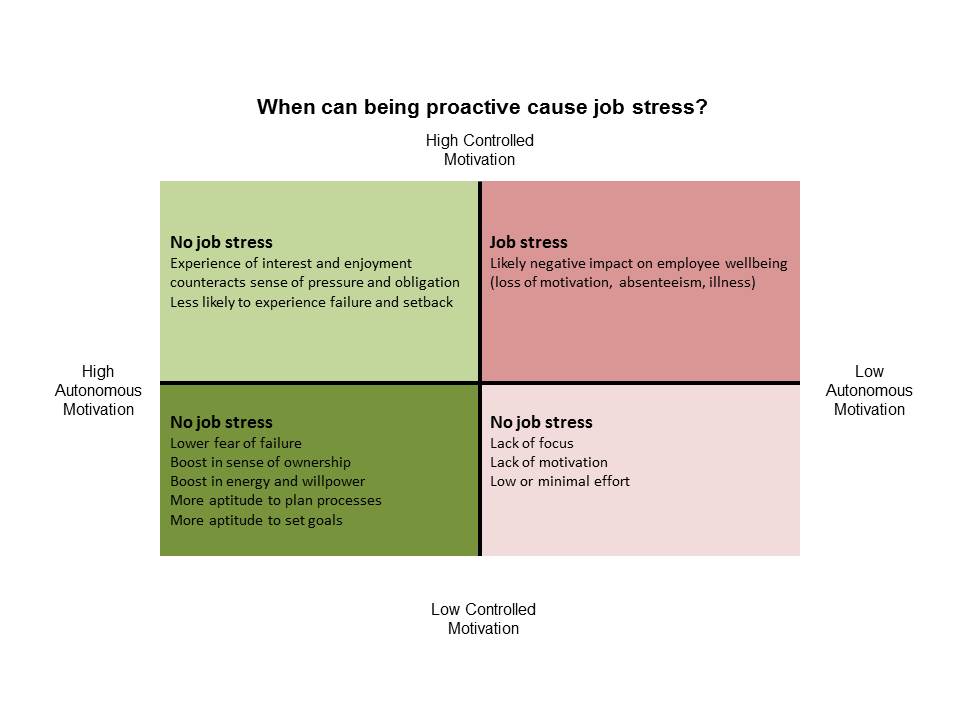

It would seem natural to think that autonomous motivation is the more likely of the two types to lead to proactivity. However, Prof. Strauss’ research shows that proactivity can in fact be initiated under various motivational states at work, even under high controlled motivation. The two types of motivation are not mutually exclusive: people can experience high controlled motivation and high autonomous motivation at the same time, or indeed other combinations of these motivations.

Targeting the right mix of motivation

The researchers found that being proactive can indeed be stressful – but only when employees experience a sense of pressure and obligation (high controlled motivation) and also lack intrinsic interest in or identification with work (low autonomous motivation). When controlled motivation was high but autonomous motivation was also high, the negative effects of the former were buffered by the positive effects of the latter – autonomous motivation providing the enthusiasm, energy, and willpower to counter-balance the depletion of resources caused by controlled motivation.

What it means for managers and organisations

Being proactive can be associated with increased levels of stress when controlled motivation at work is high and autonomous motivation at work low – but not under other combinations of motivations at work. This means that proactivity mostly does not have a negative effect on employee wellbeing and likely has other benefits including overall performance and a sense of achievement.

For organisations and their managers, this clearly points to the need to analyse how they drive change via their workforce and the motivating factors that steer employees from the ‘have to’ to the ‘want to’. In order to foster proactivity in a way that does not increase stress levels, they therefore need to promote high levels of autonomous motivation through job design and goal-setting that encourage employees’ sense of meaning, competence, impact, and choice.