With Anne-Claire Pache and ESSEC Knowledge Editor-in-chief

In their new book “Vers une philanthropie stratégique” (Odile Jacob), Anne-Claire Pache and Arthur Gautier adapt the philanthropic model developed by Peter Frumkin (University of Pennsylvania) to a French context and explain how to develop a philanthropic strategy that can optimise one’s positive impact on society. In this interview, they share key insights from the book and discuss how philanthropists, be they beginners or experts, can make use of these takeaways. Because it’s not just about “doing good”, it’s about “doing it well”!

Julia Smith, Editor of ESSEC Knowledge: What do you mean by “strategic philanthropy”?

To start, it’s important to understand that when we say philanthropy, we mean all voluntary donations by private actors (individuals or organizations) for the common good. The word “philanthropy” generally refers to an organized approach (for example, the creation of a foundation or substantial, repeated donations). When we talk about giving to others, we often think of emotion, of spontaneity, of reacting to requests. The idea of “strategic philanthropy” offers another vision of generosity by applying the notion of strategy to a domain where such a concept is rarely used.

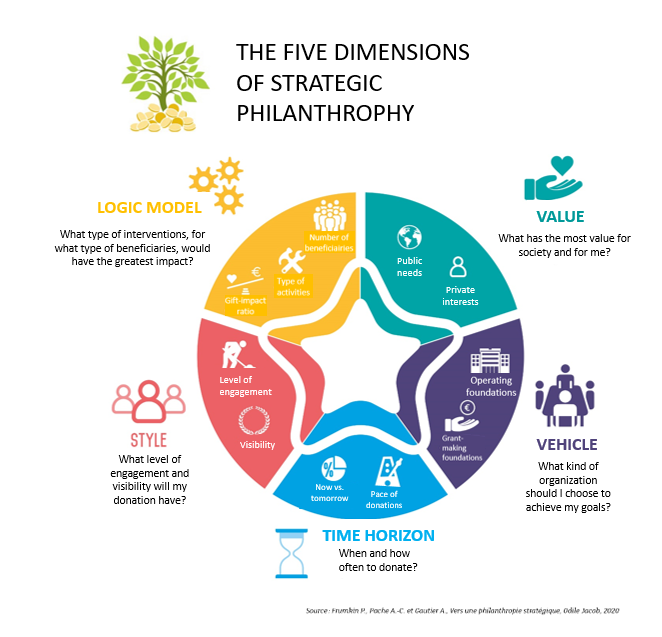

The concept of strategy has its roots in the military and is widespread in management. In its simplest form, it consists of defining goals and finding the means to achieve those goals. While there are countless books on business strategy, until recently there were virtually none that tackled strategy for charitable or nonprofit organizations. This changed with the publication of Peter Frumkin’s book, The Essence of Strategic Giving, that we have now adapted to a French context. The main thesis of our work is that to be “strategic”, philanthropists must answer five main questions: 1) what has value, for society and for me? 2) what kind of interventions would have the biggest impact? 3) what level of engagement and visibility do I want to have? 4) When and how frequently should I donate? 5) What kind of vehicle should I choose to channel my giving?

JS: What does such an approach look like? Do you have examples of strategic philanthropy?

There is no one strategy that is better than all others and that can be replicated everywhere. The central idea of the book is that there are many ways to build a strategy that satisfies those five main dimensions. The way that philanthropists think of and develop their strategy to address each dimension is just as important as the strategy they ultimately adopt.

An interesting example we discuss in the book is that of Atlantic Philanthropies, the foundation created by Chuck Feeney, an Irish-American entrepreneur who became a billionaire in the 1980s with the sale of his company Duty Free Shoppers. By nature modest and discreet, Feeney anonymously supported progressive causes until 1997, when his identity was revealed by a New York Times article. Convinced that the causes he supported (human rights, social injustice, public health…) immediately required help before they deteriorated further, he adopted an approach called “giving while living”: spending his foundation’s assets during his lifetime, rather than donating only the revenues from these assets and letting the foundation survive him. To that end, he decided in 2001 to donate the entirety of his fortune progressively until 2016 and to permanently shut down his foundation in 2020. Atlantic Philanthropies distributed more than eight billion dollars, which permitted it to finance “big bets”: ambitious gambles on a few high-impact projects.

While Chuck Feeney was extraordinary given the sums involved and his unusual choices, he illustrates the idea of philanthropic strategy with his coherent approach to giving: his values and personality aligned with the simple and discreet style in which he acted, and the present-focused timing of his philanthropy was reflected in the logic model and the vehicles he set up at Atlantic Philanthropies.

JS: Why is it important to be “strategic” when giving? Is there a problem with giving spontaneously and without a defined strategy?

In 2019, the incredible outpouring of generosity following the Notre-Dame fire in Paris was swiftly followed by controversy surrounding the donations given by the wealthy and corporations: was it not too much money? Are there not more urgent causes, in which human lives are at stake? Can we be certain that these pledges will be honoured and if yes, when? Who will receive and use the money, and to fund what exactly? Aren’t these billionaires above all searching for fanfare and positive press? These questions recall the five central dimensions of our book: value, logic model, style, time horizon, and vehicle.

The critics appear when a philanthropic engagement seems hasty, poorly planned, or likely to have negative effects on the beneficiaries and society. The critiques may not always hold water, but they do sometimes point to a lack of strategic thinking. Certainly, not all philanthropy needs to be strategic: the world will always need spontaneous donations, inspired by moral principles or in reaction to natural catastrophes. However, adopting a strategic approach is important when you want to maximize your impact and when there are substantial resources at stake. This is the case for the majority of foundations, which are confronted with challenges regarding the effectiveness, accountability, and the legitimacy of their actions within a democratic society.

JS: How can one get involved in a strategic philanthropic approach? What are the steps to take for those who want to optimise their philanthropic impact?

Strategic philanthropy is an ongoing process and a path upon which a person can embark at any time. That being said, it is easiest to ask yourself these five questions before making commitments that may be harder to change later on, such as creating a foundation with a specific mission. The five dimensions that we discuss in the book do not have to be considered in any particular order. Some philanthropists may start with a very precise idea of the general cause they want to support, while others start with a clear vision of the visibility that they want to have. What matters is to think through each dimension and then how to build a coherent approach that will address all five. In the end, developing such a strategy requires time and energy, and it is thus important to share the work with others: close friends and family, other donors, professionals with expertise in one or more dimensions, etc. Philanthropy isn’t just a solo adventure, it can benefit from collective intelligence!